TRANSITION INTERVIEW #20: Casey West.

The Long Road to Peace After Combat in Afghanistan, Outlaw Motorcycle Gangs, and a Terminal Brain Cancer Diagnosis.

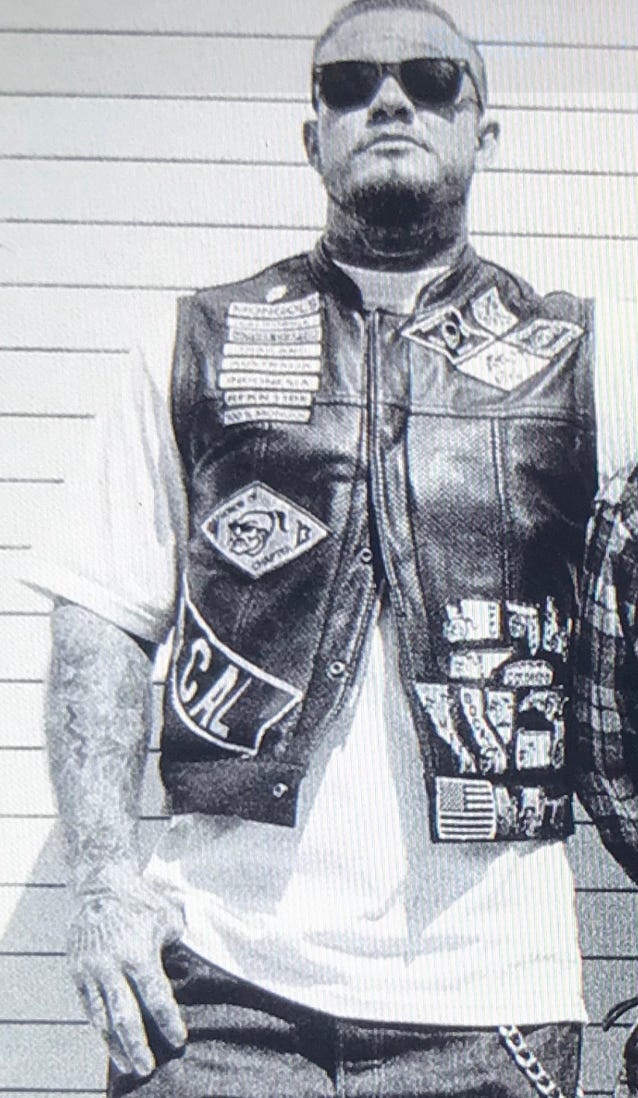

I recently had the privilege of a sit-down conversation with Casey West – Marine veteran, former member of the Mongols motorcycle club, and glioblastoma cancer survivor.

Casey comes from a generation of Americans who witnessed 9/11 at a young age and chose to do something about it. Enlisting in the Marine’s at 17 led him through combat, addiction, betrayal, and ultimately, a diagnosis few survive.

This conversation captures TRANSITION in its rawest form. From a life shaped by violence to one of service. From questioning his will to live to the deepest appreciation for life itself.

I hope you enjoy

It's great to meet you. You were a helicopter gunner, a door gunner in the CH-53? Why did you decide to join the military in the first place?

I'm thirty-four now, so fifth grade when 9/11 happened. I remember listening to it on the radio; everyone was crying. I remember thinking, someone attacked us – I have to go make sure that never happens again.

I decided that in fifth grade.

And so you went. Right after high school? Where did you grow up?

I grew up in Richmond, VA, for the most part, and yeah, I joined at 17.

Barely made it. I had to fight pretty hard just to get into the Marine Corps.

I had this alcoholic stepdad I was dealing with at the time, violent childhood, I'd been kicked out of the house, all this shit.

But I finally made it.

Was Aircrew, helicopters, being a door gunner, something you sought out?

Not really, I watched Black Hawk Down as a kid. That was a lot of it.

I was in Mogadishu once – got to go see the crash site and everything. I wonder how many people have joined the military because of that movie.

So, you start as a mechanic and then become a door gunner? The door gunner in a 53 has a pretty big job right? The way the helicopter sets down, the pilot can't see very well. Is that right?

Exactly. We're the side mirrors and the rearview.

When the bird's landing, the pilot has no visibility as to what's happening behind them. One pilot's on the sticks, the other's watching instruments. It gets pretty complex, low-light, brown outs. You have night vision, but you know how it goes, "this part of the ground is a little darker than that part."

Then you add in combat. Rockets being shot at the helicopter, machine gun fire, they would put IEDs in some of the landing zones. It's a lot.

On top of all that, you have mechanical shit. It's not just IEDs; some fluid leak or a missing bolt can take you out.

Did you enjoy it? Did you enjoy combat?

Well, the first deployment, I was a mechanic. Working on the base, working on the aircraft, getting my qualifications taken care of. On my second deployment, I was on the bird. Flew 94 combat missions.

It's a rush, you know? Parts of it I loved. That second deployment we were much more busy. At the time, you had the drawdown – Obama was pulling people out. We had a much larger area of operations and a lot fewer people to cover it.

A lot of guys were getting fucked up at that time. I remember this unit of Australian guys… Their whole operation got shut down because, basically, all of them died.

We were doing a lot of narcotics operations. Afghanistan has a lot of opium, right? Tons and tons of Afghans – farmers – make their money off those opium fields. Well, when the Taliban said "No more. No more opium exports."

I'm not a conspiracy theorist, but I'm telling you, so much of what we were doing was concerned with who controls those fields. And a lot of people got killed because of it.

And was that part of the reason you got out? Ethical concerns?

No. I had a lot of questions. Some of it bothered me, but that's not why I got out.

I loved the Marines. Looking back, I was addicted to the fighting part. That feeling, the intensity, the mission.

I had a wife at the time, also a Marine. While I was deployed, she decided she no longer wanted to be married, and she knew how to manipulate the system to make me look bad.

I don't want to talk bad about her now, but basically, I got home, I'd been in all this combat, and all the sudden, I'm in this battle with my wife, looking at divorce, dealing with the big Marine Corps, and literally weeks later, I was watching people die on the battlefield.

I was so angry. None of it made sense to me. I'm supposed to be doing all the things you should be doing after a combat deployment, and instead, I'm looking at all this disciplinary shit.

I started drinking and doing drugs. I'd take off for a week at a time, going back to Richmond. Anyway, I was at the end of my enlistment, so basically, they said, "Your time is almost up anyway. Just do what you need to do for a few weeks and you can leave the military."

I'm sorry to hear that. That's not a common story, but unfortunately, it's not uncommon. Did you have any ideas for what you might like to do with the rest of your life?

I had zero plans. I thought I was going to die on that deployment. I wanted to, really.

Why is that? Or, what makes you say that?

I had such a rough childhood. I survived child abuse, voilence, drugs. I had friends who got killed, committed suicide. I didn't really expect to be alive as an adult.

Then I'm in Afghanistan - you see good human beings getting killed. You start to wonder, 'Why do I deserve to live, and these guys don't?' You think about home, what home life is like, how it's sort of combat in its own way.

I thought dying in combat… It'd be a lot better than some of the other ways to die. You know?

So, what did you do when you first got out?

I moved back to Richmond. Bartending. I thought maybe I'd become a psychologist, maybe try to help other people with bad childhoods. I had no idea what to do.

I started drifting. I met a guy who was a Marine and also happened to be part of the Mongols, the motorcycle gang.

He took me under his wing in a way. Just like that I'm inching toward that life. The criminal underworld. (laughter)

I can guess, but what enticed you about that world? What's the best thing about being in the Mongols?

Camaraderie.

You go from ripping around on helicopters to ripping around on motorcycles.

I was on that bike all the time. I rode from Richmond to Rosarita and back. Everywhere.

I could go all around the world, knock on someone's door, and he'd welcome me in his house - that's my brother you know?

Now, are we really brothers? No. Turns out, a lot of that is surface.

What's the worst part about club life?

That life is really cutthroat. A lot of politics. I got kicked out because I was… I was a warrior, as they say. I wasn't a politician.

Skipping ahead, but I got promoted to "Mother Chapter." The top-level which sort of manages each of the local chapters. So, as you can imagine - it was more combat, really.

You're constantly watching your back. You're in a club that claims to be a brotherhood… But you've seen the tv shows and that shit. You're constantly watching your back.

Is it possible to be in a club like that and just hang out? Not be involved in the politics and whatever crime might be going on?

Oh yeah. Absolutely. Just like the Marines.

That's most people. Most people want to look cool and hang out at the bar, drink beer, and this kind of thing.

1% clubs man...To be honest, a lot of it is a joke. You start to look deeper, see everything that's going on. It's hardly brotherhood. They get these guys that need something, they need family, they're hurting… Just like I was… And they exploit these people.

How long did it take you to realize that?

Few years. I started prospecting in 2016, and I got kicked out just under three years later.

I was seeing things that I couldn't let go. Things I wasn't okay with. I started asking questions about different things, and that's what started my demise.

Is it life-threatening to get kicked out of a motorcycle club?

Can be. Depends on why. If you're a threat to the club - definitely can be.

I just met you, but you seem like someone with a lot of awareness, someone who thinks a lot about the morality of organizations and war. I can tell you've given a lot of thought to this type of thing. Is that retrospective? Did you think about these things while you were participating?

Some of it. When I started getting sick, obviously, you start to think a lot about the meaning of life.

And were you sick while you were still in the Mongols?

Really sick. I started having hallucinations in 2016 - no idea I had a brain tumor.

I went to the VA in Long Beach, they told me I had PTSD, schizophrenia – basically told me it was all psych problems.

I was telling them, "I'm not crazy. I know I'm not crazy."

I was on death's doorstep. In so much pain. Migraines. I lost sixty pounds. Really sick.

To deal with all that, you know, I was still in the Mongols. I was basically welcoming death. A couple times, I'd go 120 mph down the Pacific Coast Highway. I had overdoses. I would take so much Xanax and pain medication that I would just be passed out for days.

Had no idea I had cancer. The whole was divine. It's a miracle I survived that last year when I was getting kicked out of the Mongols.

And the VA, they didn't think to give you a brain scan? They weren't taking you seriously, or what?

No, they didn't take it seriously. They wanted to treat the migraines. I had other injuries, shoulders, abdominal injuries… Other things that distracted from the real issue.

At this point, I was out of the gang. Still sick all the time, with constant migraines. But I moved to Texas, and I was working on this farm. I started eating healthier, doing meditation, this kind of stuff. When I got away from the club life, all the drinking and drugs and all that, I thought I'll start taking care of myself and that will take away my pain.

Finally, in 2022, they found the tumor, and I was diagnosed with Glioblastoma.

And what did the oncologist tell you? Were you expected to survive?

They told me, "You might have thirty days, you might have three months."

They said with chemo and radiation, I could maybe make it 12 months.

When they pulled the tumor out, it was encased in cist, which prevented it from spreading through the rest of the brain.

What's interesting to me is that in a few years’ time, you go from someone who's doing recreational drugs and, as you said, speeding down the highway to someone who is now extremely dedicated to taking care of their body and mind.

Did the cancer diagnosis shift your perspective? To think, okay, I really do want to live, and I'm going to beat this?

In a way, you're right. These guys told me I had terminal cancer; they told me I was going to die. I saw it as a challenge. I took control of my health. And it's a process; I'm still working on it today.

But yeah, it's all connected. I shouldn't have survived childhood; I shouldn't have survived Afghanistan – flying around getting rockets shot at you. I shouldn't have survived the Mongols.

So, when the doctors told me I wouldn't survive cancer… I thought… We'll see.

I know you've embraced a lot of lifestyle changes and researched your own healing methods. Do you feel like you just have the intuition to know where to embrace standard cancer treatments and where to chart your own path?

I try to educate myself about everything.

I lost a lot of trust in the medical system, obviously, given how long it took the VA to take my symptoms seriously. People have been rude; I've seen doctors become very disrespectful if you even question their chemo protocols and whatnot.

I just pay attention to the details. I ask questions. I started to look at… How does fasting affect the body? How do alcohol and various substances affect the body, and how does all this work?

And now, this is my purpose. Helping other people, inspiring people. Vets.

What does today look like for you? You look healthy. What are you looking forward to in the future?

It's still a battle. Every day, I'm working on my health. Working getting on being a better person.

I want to start a non-profit. I'm not sure if you're aware. The aviation community has the highest incidence of cancer of any profession, by a long shot.

They've got all that imaging and radar systems in those aircraft. The FLIR system and all that shit puts off a ton of radiation. That's not even considering the toxins you're exposed to working on helicopters.

So, I want to start something. Help our guys. Help other people with Glioblastoma.

That's amazing, and I have seen some research on aviators and air crews and the level of radiation exposure.

Some vets will read this. When it comes to health, what would you say is fundamental? Maybe three core changes people can make? There is so much health and wellness advice available right now - it can be overwhelming.

It's incredibly overwhelming because everywhere you look is another expert saying, "Do this, or don't do that." It's not realistic.

So much of it, the physical side has to do with detoxification. Diet. You have to look at what you're putting in your body – be it sugar, alcohol, or processed foods. It all matters. Then you have detox techniques – fasting, sauna, cold plunge, things that repair the body.

Then, on the mental health side. Pay attention to the energy component. Everything you interact with has energy. Music, the news you watch, your relationships, the outdoors, workouts, it all gives you positive or negative energy.

A lot of people will say they're unhappy or depressed, but at the same time, they're subjecting themselves to so much negative energy.

Do you get bored these days? You've lived a high-intensity life.

No. Being so close to death, I have so much appreciation for life.

It's going to make me tear up to explain it to you… I have so much joy in life, and I think even though I've had a hard life, I really appreciate life. And I mean that.

In Afghanistan, we would take these platoons in, drop them off – we'd take in 10 guys, brothers, friends, guys who just signed their life away to the military. Five hours later, we'd pick up 9 or less, maybe.

All the bad shit I've done? And what did that guy do to deserve what happened to him? Nothing.

We can't lose sight of that. So, I stay focused on that, and I'm just appreciative.

Casey, thanks for doing this. I have a ton of respect for you and your story. Keep going.

You too. I enjoyed it.

Thank you both for this interview. We need these real life stories now more than ever. God bless you both.

This story is raw and filled with perspective and emotion. Thanks for sharing.