TRANSITION INTERVIEW #16: Sebastian Junger.

Returning From Korengal, America's Need for Greater Community, Risk, and Thoughts on the Current State of Journalism.

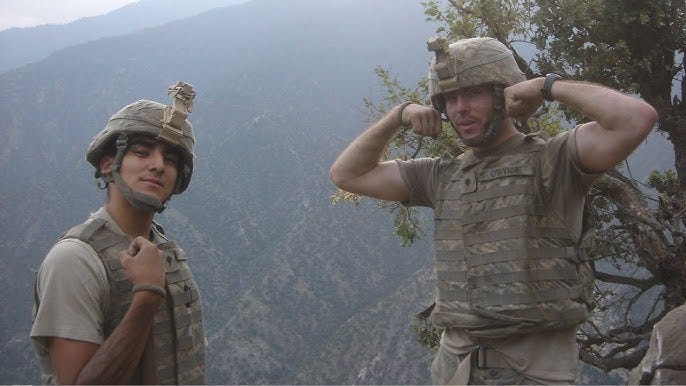

Sebastian Junger is an author and former war journalist. In 2008, Junger and colleague Tim Hetherington spent a year embedded with the 173rd Airborne at an outpost in the Korengal Valley of Afghanistan - an experience depicted in the 2009 documentary film, “Restrepo.”

Junger is the author of “The Perfect Storm” which was adapted into a major motion picture. His 2016 book “Tribe" explores the deep human need for belonging and community, particularly through the lens of soldiers.

In 2021, Junger wrote a travel memoir titled “Freedom” after walking 400 miles along Pennsylvania’s rail lines, concluding that modern life has not made people feel safer or more content in their lives, and that lacking interpersonal bonds have contributed to the rise of anxiety, depression, and suicide, especially among wealthy societies.

Following an abdominal bleed that nearly took his life, his latest book,“In My Time of Dying” is an exploration of near-death experiences and the idea of an afterlife.

Weeks ago, I wrote something about Combat Outpost Keating in Nurestan Province, Afghanistan, a particularly hostile place. A handful of people commented, people who'd spent time there. Many expressed the same sentiment.

One person wrote, "Oddly, I miss the hell out of that time in my life. I miss how simple it was, how close to death, but also how alive I felt. It was horrible, and I would also go back in a heartbeat."

Do you ever share that sentiment? Nostalgic about seemingly dangerous times, be it the Korengal Valley or otherwise?

Yes and that response doesn’t surprise me.

I studied anthropology in college, so think about these things through that lens.

We’re all social primates, adapted to existing in challenging circumstances and surviving in collaboration with other humans. Historically, if you were left on your own, you die. Humans don’t survive alone in nature - at least over the long term.

American individualism, you know, it's comfortable but also inconsistent with who we are as a species.

The way to feel safe in the world, and I mean this in every sense of the word – physically, emotionally, and socially safe – is to provide something to your survival group that they need. Otherwise, you yourself are at risk.

If you're the only guy who can chip arrowheads, no matter how obnoxious you are, you're not going anywhere.

So, you take a platoon in combat, which happens to be the same size as our typical human survival group - when you're a part of that platoon, you've produced almost exactly our evolutionary past, and that feels really good.

Most things that are adaptive feel good - because they aid in our survival. Eating when you're hungry feels good, that leads to survival. Sex feels good, that leads to reproduction. When you find yourself contributing to a small group, contributing, it feels good. Even when it sucks, it feels good.

You remove a person and place them in the great American suburb, there are two problems. First, it's too easy. All these skills you have are no longer needed. And second, no one is reliant upon you.

Maybe you play rugby once a week with buddies, but no one's survival depends on that. It doesn't matter, really.

So the result is anxiety, depression, "what's the point of all this" which is a form of suicidal ideation, all the things you described.

To me, it makes sense that we feel that way.

Sure. It's not as odd once you zoom out. Is re-immersion, re-integration something you always understood? Something you’ve always been conscious of? How do you think about your own re-integration process?

Well, most of my war reporting was not with the U.S. military. My first trip to Afghanistan was in '96. I was with Massoud in Kabul (Massoud’s Last Conquest, Vanity Fair) right when the Taliban was coming to power.

Then, Sierra Leone, Liberia, and Bosnia in the early nineties.

So, my TRANSITION struggles were different, but they were significant. If you're in war, you see bad things, and bad things might happen to you. It takes time to recover from that.

It also takes a while to recover from a car accident, a divorce, or losing a brother to cancer. Soldiers don't have a monopoly on trauma.

Often, I’d return from a trip, I could tell something was off. This was before PTSD was talked about, before 9/11. I was anxious in bars, in the subway, freaked out on a ski gondola once. I was forty years old. I thought I was going crazy.

It took me a while, but I realized this is classic trauma response. Situations where you're not in control.

Eventually, I realized that episode in the ski gondola when you freaked out for no reason. That was because weeks earlier, you watched a dozen guys get drug out of a minefield – all missing their legs.

Bun in the Korengal Valley, I didn't see gruesome things like that. A few, but in a way, it was fine. Some close calls. But the guys in the 173rd Airborne were outstanding soldiers.

I remember thinking we were in combat, but they got this.

I expected I wouldn't have such a reaction when I got home from that trip because the trauma was relatively low compared to other places.

But that's not what happened.

After Tim and I made Restrepo, I realized what we're all experiencing isn't a trauma response; it's grief.

I really affiliated with the platoon I was with. For the first time, I'd been woven into the fabric of the tribe. I was trusted, I was relied upon, and it was an honor to be part of it. It was everything we're adapted to want as humans.

That’s intoxicating. And when I got home, I bottomed out. Real depression.

When I realized all the other guys in the platoon were having the same reaction. It clicked. This was actually a very healthy reaction to being deprived of something consistent with our evolutionary past.

I was taken out of that and put in something unnatural and so safe which isn’t normal.

Home, the safety of home, it's a blessing in some ways, but that TRANSITION is certainly not natural.

Much of your professional work has been abroad and much of it pretty adventurous – dangerous by comparison. How do you find the time between those adventures, participating in regular life? Do you still long for that kind of work?

I got out of war reporting at age 50 when my friend and colleague that I made Restrepo with was killed in Libya. He was hit with shrapnel from a mortar and died in the back of a pickup truck.

After that, my marriage fell apart, several things happened, and I had to sort of reset the odometer. I got married again and eventually started a family.

Had I TRANSITIONED out of that life at thirty, I might have missed it enormously. But, as you go through life, different things are meaningful at different ages.

If you're living a quiet, sedentary life at twenty, you might be missing out on some young man stuff - young woman stuff. If you're still dodging bullets at sixty, you might be missing out on some old man stuff. Right?

The world's a beautiful place. If you're always chasing war, or if you end up with a bullet in your forehead, it's not such a beautiful place.

If you can't appreciate the beauty and the profound nature of the world in its quiet forms, then appreciating it in its more dramatic form is kind of bull shit. You're missing it.

I'm lucky because I did that stuff when I was young and got out. Reluctantly. I wasn't sure what my identity was if I was not a war reporter. Like many soldiers, you could probably answer that better than I could.

Eventually, I started to see the shallowness of that perspective. Constantly trying to make yourself happy.

I was 55 when my first child was born. That was the most profound, exciting, and meaningful thing that ever happened to me.

I might not have appreciated that at thirty. But I do now.

And have you found it difficult to find things to work on? Outside of raising your children.

Sure. It was much more difficult when I was younger, but now I can.

I knew a guy who was much older than me. Very wise man. A chimney builder who lived on Cape Cod. He spent his entire life on this narrow peninsula of sand. Name was Conrad.

One day, I said, "Conrad, no offense, but do you ever regret spending your entire life in this tiny place?"

I remember being nervous when I asked him that. I waited for him to be offended by my question.

He says, "No. Because I learned to see the infinite in the minutiae. Everything you're doing, looking at, it's incredible."

I think there's some real wisdom there. Just the fact that you exist, that you're alive - it's very unlikely, and if you can appreciate that, life gets easier.

Anyway, that's something I would have dismissed as a younger man, but I can appreciate it now.

How do you think about transformative experiences when it comes to your children? Going abroad and being in the military, all of that was formative in my life – but it was also dangerous in ways. Do you plan to encourage your daughters?

Well, no parent wants their child dodging bullets. But people die doing all kinds of things. Risky or not.

I'll encourage them to take risks. But take risks where you can control the variables. Not to play Russian roulette.

Risks should be meaningful and not random. I'd want my kids to take risks where there's some reward that comes from it – some learning, something new, some value.

We plan to take trips, live in Africa and Mexico, take them around the world, and expose them to the fact that American society, the American way of life, is not the only one.

Perhaps it's not even the best one.

You can make some pretty powerful arguments that it's actually not particularly good for people – measuring by mental health statistics.

Veterans will read this, but some interested in writing as well – I hope. What advice would you have for someone early in their writing career, looking to find their sound, their style? When it comes to pace, sound, voice - how did you come about your own?

I never studied journalism, but I read a lot of good writing. Peter Mathieson, Joan Didion, John McPhee, the list goes on.

You know, I was a long-distance runner in college. Running is all about efficiency. Your body gets more efficient, and the mechanics improve the more you run. If you do 50 miles a week for years, your body finds efficiencies.

A coach can tell you not to swing your arms, but that doesn't work well.

Same is true of writing. You find your style by writing a lot.

You don't choose a style, and you don't get given a style; you get there by crawling on your hands and knees up the mountain.

You've mentioned a quote you admire: "Journalism doesn't tell you want to think; it tells you what to think about." Is there an outlet or person in journalism that you really admire right now?

Man, I don't know. All of cable news is out.

Fox News is particularly bad, CNN is not as bad but still excludes itself from the news category because of such an insistence on leading the witness, even at its own demise.

But these really aren't journalists; I don't know what they are. Reality television or something.

C-SPAN is pretty straightforward. (Laughter) There are some good shows on NPR, but they also can have some insufferable liberal bias.

I'm a Democrat, but liberal bias… I hate liberal bias; it makes my skin crawl. I don't like conservative bias either, but liberal bias is particularly bad – it has this whiff of moral superiority that just drives me crazy.

I don't know what to tell you, really.

(Laughter) That's why I asked, I don't have an answer.

The New York Times, the front section, and the Wall Street Journal's front pages can be pretty straightforward. The opinion sections, though, can be pretty obnoxious.

The National Review is conservative. Again, I'm a Democrat, but I'm willing to tip my hat to conservative publications that I think are straightforward, not tipping the scale, not leading you to their ideas…

Those three aren't bad. I read good stuff writing in the Atlantic and Newsweek, but there's also a lot of bias there.

People are much smarter than a lot of journalists want to believe.

I'll give you a tip. Every newspaper is, in one way or the other, affiliated with the right or left. A few aren't, but generally speaking.

People call the NYT a liberal newspaper, and they're right; it is. But they're at least willing to criticize the liberal establishment. I mean, they excoriated Biden, the guy who was, quote, "their president", right?

Point is, what should be really alarming is any outlet that never criticizes their own camp. Fox News is particularly bad about this. If someone refuses to criticize their side. That's not news; that's a propaganda arm.

Last one, if someone came to you and said, "Sebastian, I'm at the end of a long military career, and I'm out next month, leaving the tribe, how do I not fuck this civilian thing up?" Any advice you have for this person?

Well, I would say the more affluent the community you live in, the lower the impetus toward connection – towards community. The less affluent people are, the more they rely on the community.

I grew up in an affluent, almost entirely white suburb of Boston in the sixties. There are some nice things about that, of course, nice people, but we didn't know our neighbors at all. We didn't need to know our neighbors because we didn't need each other.

I now live in a mixed-income neighborhood on the Lower East Side of New York. People rely on each other. Everyone is entwined here. It's a real community.

So, my first advice is not to move to an affluent suburb. If you want to be a depressed alcoholic, move to a wealthy suburb.

Lastly, give up the idea of reproducing the thrill of combat. It's not realistic. Right?

If you think that's the way to be happy in civilian society, you'll never be happy. And if you consider yourself to be in some way superior to everyone else because you were in combat – you'll never TRANSITION home – because who wants to TRANSITION to an inferior population?

You have to give up that sense of specialness. That specialness helped you survive in a combat environment; it was useful. But the same thing will end up impeding your life in an ordinary existence.

That's really good. SEALs, in particular, Special Forces types, I sometimes see us working so hard to maintain some "operator" type relevance long after our departure from active duty. Reluctant to give it up or to move on to whatever's next.

Certainly, and that's not unique to military folks.

Listen, Sebastian, I think "Tribe" is one of, if not the most recommended and referenced books in the veteran community. I really appreciate you doing this and the work you do. Thank you.

Great interview, Benjamin! I've been a huge fan Sebastian's work for many years. Love reading his TRANSITION experience. I loved the Cape Cod fella's quote of "Finding the infinite in the Minutia". Powerful advice. Thanks to Sebastian for sharing that nugget of wisdom, and thanks to you for hosting these conversations!

Another amazing and insightful article. Great advice that can be applied to all walks of life. Thanks for staying dedicated to these TRANSITION interviews! My guess is that these articles mean a lot to a lot of folks.