Rethinking "Imposter Syndrome" following military service.

Four strategies that reframe how we think about our value as Veterans entering the civilian sector.

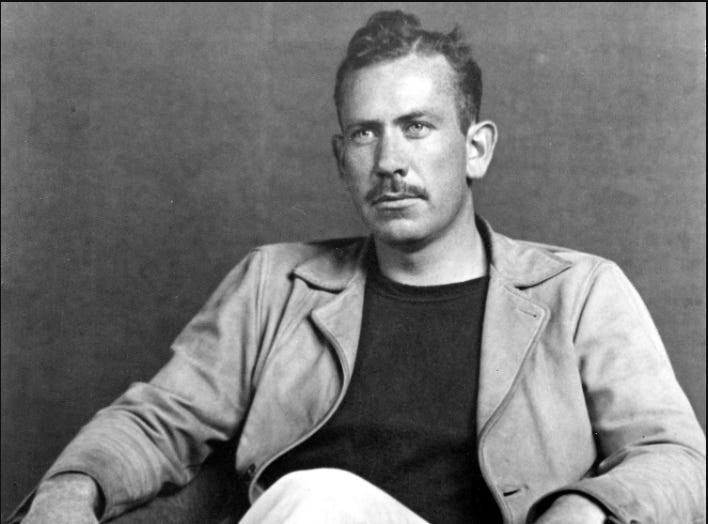

John Steinbeck is the only person to win both the Pulitzer Prize and the Nobel Prize for literature. Before becoming a writer, Steinbeck spent 20 years amongst California's migrant labor force, working ranches, harvesting sugar beets, and working manufacturing jobs. He would eventually write the two highest-grossing novels to come out of the Great Depression, Of Mice and Men and Grapes of Wrath, but only after dropping out of Stanford and surviving on whatever fish he could catch in the Monterey Bay.

In 1961, after publishing 15 novels, Steinbeck wrote in his journal, "I am not a writer. I've been fooling myself and other people."

Steinbeck, like so many others, struggled with the yet-to-be-named "Imposter Syndrome," an internal experience recognized by the American Psychological Association as "a belief that one is undeserving of a particular position, status, or role, commonly presenting as self-doubt despite prior education, experience, or accomplishment."

According to a 2019 review of 62 studies on "Imposter Syndrome," as much as 8% of American workers claim the presence of the experience to be constant, and 82% claim to have experienced "Imposter Syndrome" at least once in their career.

For recently separated Veterans, conditions are well set to experience a period of Imposter Syndrome. Aside from Government Services roles or a civilian role within whatever community we served on active duty, it's likely that Vets will face an enormous volume of new information and navigate many new processes in their first role post-military.

Fifteen months after I separated from the military, I found myself in a new role at a large tech company. On top of cultural differences and learning to navigate a firm of its size, I'd accepted a role as a "specialist" within cyber security. The work was nuanced, technically in-depth, and involved layers of complexity. The amount of information I thought I needed to retain to "know what I was doing" seemed impossible. A few months in, I determined I'd fooled the hiring manager. For a year, I experienced Imposter Syndrome. Combatting an ever-present voice, telling me, "These people know you don't know what you're doing."

Eventually, by communicating with other Vets, I was able to reframe the experience. I doubled down on a handful of strategies and slowly but surely found some relief.

Find someone who will tell you the truth. If any one thing helped reduce my feeling of being an Imposter, this is it. Feedback loops are present in all civilian organizations; however, many withhold honesty, and none are as raw and uncensored as what exists in the military. Once you realize this, it can be pretty uncomfortable. The only thing worse than being convinced that you're underperforming is being convinced that everyone around you sees you as an underperformer but is too nice to say anything. With no honest feedback, creating your own uninformed narrative about how things are going is easy. Instead, invest time in a relationship with someone who does know what they're doing. Let them know you welcome their feedback and criticism. Invite the conversation. Even if painful at times, you're better off with the opinion of someone informed than you are creating your own uninformed narrative.

Find time for what's important, not urgent. I recently learned of a concept called the Eisenhower Box. A model for identifying tasks in one of four categories: non-urgent/not-important, non-urgent/important, important/urgent, and urgent/non-important. Much can be said about each category; however, the point is, as Vets in a new role, we must make time for "non-urgent/important" work. This work drives our development and ability but does not have to be done today. I've spent weeks executing tasks that are almost exclusively "urgent/non-important", generally "to-do lists" that have little impact on competency. "Non-urgent/Important" is deep work, time for educating yourself on less-familiar subjects, building relationships, and critical thinking. Things that won't move the needle today but will make a difference over the long term.

Be able to articulate your value. As a Veteran, your experience brings value to your new firm/role, that is undeniable. Despite your suspicion that you may have oversold your talents to your hiring manager, you add value in many ways where civilians do not. The sooner you accept this truth and spend time identifying what YOU specifically bring to the table, the better you'll identify the types of tasks and projects to involve yourself in. If this feels challenging, perhaps find a Veteran who has been around for several years, share the details of your military career, and identify where those experiences exist in your current role. I assure you they exist.

Volunteer for yourself for the less desirable tasks. I can recall being new in role and feeling as if I was only receiving advice and had not once provided it. It's easy to see how this encourages "Imposter Syndrome," as it can be hard to feel as if anything depends on you. However, this issue also exists in the military. As a junior SEAL, more senior SEALs are critical to your development. They will need to invest significant time in you should you have any chance to succeed. In that community, junior SEALs overcome this period of disproportionate value by volunteering to do the least desirable tasks. Taking out the trash, prepping ammo, cleaning weapons, etc. This exchange can also be performed in the civilian world.

Think about what can be done to reduce the workload of those who invest their time in your success. Where are those obnoxious tasks that everyone must do, but no one enjoys? Where can you make life 15% easier for those willing to help you, not to settle the score, but to show that you wish to reciprocate their efforts?

Understand that new vernacular is simply that. Lastly, avoid attaching any part of your self-assessment process to how much vernacular you do or don't comprehend. The civilian world, especially the tech industry, is overrun by fancy terms, buzzwords, acronyms, etc., and the military is no better. Imagine if, when you were serving, a highly sophisticated civilian was brought into your team to work alongside your team. Regardless of their intelligence, the burden of comprehending vernacular would be enormous. However, that would say nothing about the person's ability to add value. The same is true for us as Vets. The new terminology is precisely that.

If nothing else, remember, if you are convinced you have everything in the world to learn or are unsure how to add value to your new role, you're in a place of personal growth. The feeling will not last forever. I assume you're adaptable, you can take on new skills faster than your civilian counterparts, and if nothing else, you'll find a way to "work smarter, not harder."

The art for this post was created by Sarah Rossetti and can be found at

https://www.invadergirlart.com/

Bravata DM, Watts SA, Keefer AL, Madhusudhan DK, Taylor KT, Clark DM, Nelson RS, Cokley KO, Hagg HK. Prevalence, Predictors, and Treatment of Impostor Syndrome: a Systematic Review. J Gen Intern Med. 2020 Apr;35(4):1252-1275. doi: 10.1007/s11606-019-05364-1. Epub 2019 Dec 17. PMID: 31848865; PMCID: PMC7174434.

Ben,

16 months into the transition and so many of these points hit home. One area that is especially hard to swallow is that you have to individually prove and understand your value. Nobody will do it for you if you don't consistently advocate for yourself. The days of automatically receiving an eval are gone. Most companies I have interacted with seem hesitant to provide critical feedback or communicate the bottom line openly. I think this is where most veterans can break through civilian norms and initiate hard discussions to add value to the organization.

Great writing and I hope more veterans continue to read these valuable lessons.

Ben,

A perspective that translates to many of us. Working with chronic illness has many of feeling the same way, a healthy imposter. Your suggestions are practical and I found them helpful. Great Writing